For about a decade now, Treignac Projet has unrelentingly pursued the development of its programme, between astute exhibitions, summer residency programmes, and invitations extended to curators, artists, art critics, philosophers, and other theorists of international renown. After a number of invitations to foreign curators to come up with what we believe are among the best exhibitions currently presented in France, it is not surprising that Sam Basu and Liz Murray, the founders in charge of the venue, asked Swedish-Canadian curator Sabrina Tarasoff (already very familiar with the place1) to devise the next part of the “curators’ programme”. So it is with the exhibition Garland that Tarasoff has chosen to start this cycle.

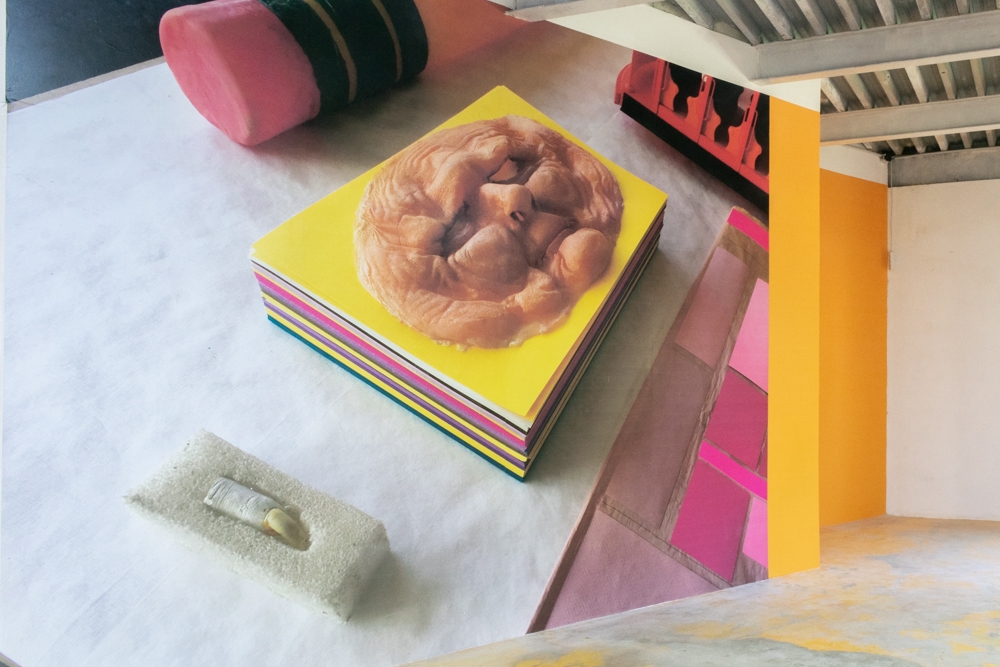

While it is thematic, Garland is not an exhibition with a thesis, and the works presented do not necessarily seek to support a curatorial message. Instead, it is more of an “environmental” exhibition, whose aim is to reproduce a spirit, an atmosphere, by juxtaposing and associating the artworks. This way of exhibiting (in vogue in recent years) is intended as holistic, in the sense that what the artworks produce as a whole predominates over individual works. Consequently, Garland is revealed like a landscape that we contemplate as a whole before examining its constituent parts in greater detail.

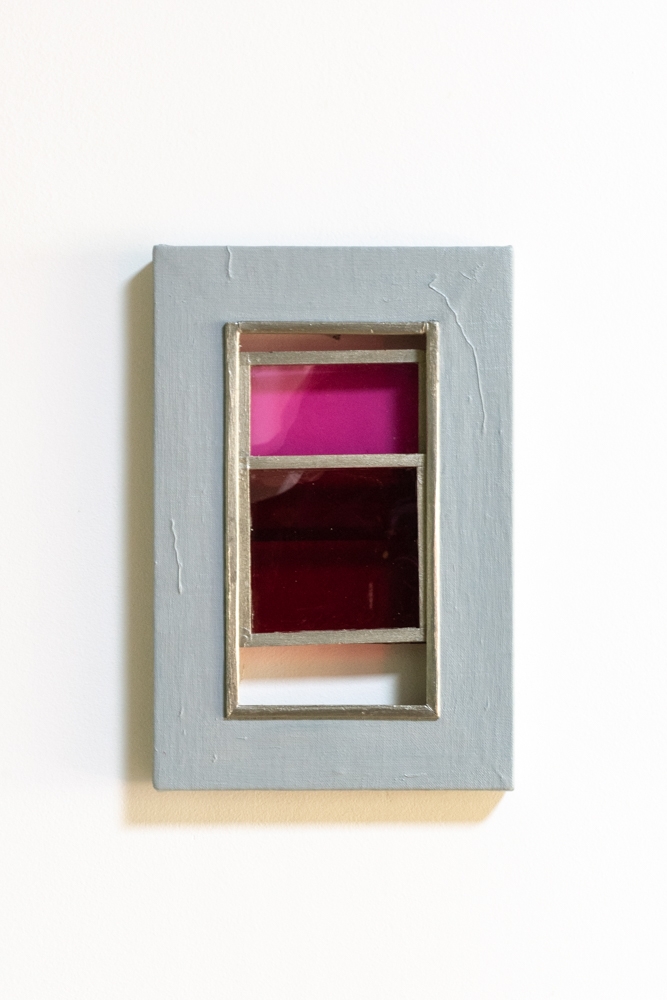

As its statement presents it, Garland aims to be polysemic: it is clearly the principle of the garland that is initially convoked, or more specifically, the fact of assembling various objects or ideas – a mise en abyme of the exercise of collective exhibition – but also different realities, with the goal of confronting them. The model of the fairytale thus becomes an appropriate tool for analysis, and if we’re talking [Judy] Garland, we’re also talking The Wizard of Oz (1939), the ultimate film-landscape. A purely studio-based production, featuring sets with painted landscapes, whose planarity still works as a perfect illusion, this film does seem to be the perfect model for both the formal and conceptual structure of Garland. The yellow colour of the original floor of the exhibition room is still parsimoniously present, echoing the yellow brick road of the film and the four wallpapers by Alex Da Corte very faithfully reproduce the colour code of the landscapes in which the actors roam. The very glittery atmosphere of the film gleams in the works of Karen Klimnik, Guendalina Cerruti, Signe Rose, or Scott Benzel, while princesses and fairies appear throughout the visit as in Ericka Beckmann’s Cinderella (1985) that we still regret was not projected to human scale as the artist recommends.2 A choice that was all the more surprising in that the exhibition invites a complete corporeal immersion within a specific world… The filmic illusion is brought back to the visitor’s attention with another artist of the Picture Generation, Sherrie Levine, whose presence recalls the principle of simulacra at work in the culture of the consumer society, active now more than ever, and confirmed precisely by most of the artefacts used in the artworks exhibited. But it is also the angelenos origin of most of the artists listed that completes the importance given here to the filmic illusion now at work in reality: because if the sublimation or mystification of the banal now seems to go without saying, there is no longer any difference between reality and fiction, an established fact that pop culture has largely contributed to provoking.

While Garland is a refined exhibition whose multiple semantic fields offer plenty of “yellow brick roads” to explore, its message nevertheless gives rise to a degree of discomfort. According to the press text, the presence of Judy Garland meanders through the exhibition like a spectre, and her figure is apparently “absent”.3 Garland is thus apparently “an homage to Judy, an attempt to hail fandom, fantasy, and the mirage of stories, whilst keeping at bay the darkness of culture’s memento mori.”… And yet, the character that she plays spends much of the film trying to get home, repeating to whoever will listen that “there’s no place like home”, a moral that encourages everyone to go home and stay neatly within the place that has been attributed to them, above all avoiding any straying from the straight and narrow that would be capable of twisting the system of an American society that was then being exported globally, particularly by way of the film industry. Hollywood’s subliminal messages, of which The Wizard of Oz is recognised as being one of the main colporteurs, would thus be unable to lend support to any statement giving free rein to fantasies and dreams. Let’s not forget Judy Garland herself, whose tragic fate has also become iconic, as a pure product of the Hollywood studios and a teenager with a tendency for portliness, who took diet pills to the point of sinking into addiction. While pop culture consciously or unconsciously produces marvels that today’s art feasts on, it is still important to stay vigilant as to the origins of the glitter sprinkled over reality.

Notes

- Sabrina Tarasoff organised a small exhibition there in 2016, with Bel Ami, entitled Demimonde and participated in several writing residencies.

- “Jim Hoberman:

A lot of ‘70s performance artists made use of video. Why did you decide to work with Super 8 sound?

Ericka Beckman:

Because you could project a film life-size in a room, and I wanted to stress the presence of the performance in my image. […] I wanted to make films that were documents of a type of performance that could only exist on film. I was invested in making an active art form, an art that moved, and that movement was the telling.” See http://moussemagazine.it/j-hoberman-ericka-beckman-2013/ - This turns out to be untrue, since a snowball by Guendalina Cerruti entitled Judy (2019) contains an image of the young face of Judy Garland.