The BioHARDCORE Capsule, which was installed at the Espace des Limbes de Saint-Etienne from 13 March to 1st April 2017, was primarily represented by its a mystical and heathen imaginary; followed by a voice, the rampant voice of Antoine Boute, an experimental poet and “pornolettrist”; and finally, by bodies, that of Chloé Schuiten, artist and sculptor, and Clément Thiry, handyman and sleeper. For the past two years, they’ve developed a performative, deliberately festive practice, which takes shape at the margins and in the interstices that are roadsides or forests, a practice that they describe as “BioHARDCORE”.

The concept sprang from Antoine Boute’s imagination, who evoked the manifesto “En avant pour la révolution bioHARDCORE” in a 2016 lecture. The manifesto is a practical manual for saving the planet at the macro-political level, by transforming all forests and wastelands into independent non-anthropocentric states, and, at the micro-political level, steering human life towards its “hardcore” level: animal, vegetable, material, nuclear.”1 “Revolution” should be understood here less as a radical change in political regime than in its original sense, revolutio meaning “turning back time”: the BioHARDCORE Revolution is an involution, a spontaneous or provoked regression of the organism to a prior state, a return to the vegetative state that Chloé Schuiten affirms: “the ultimate would be to stop everything, to do nothing useful and productive but dedicate ourselves solely and entirely to being no more than a body that is extremely, appropriately, and specifically in connection with its environment.”2

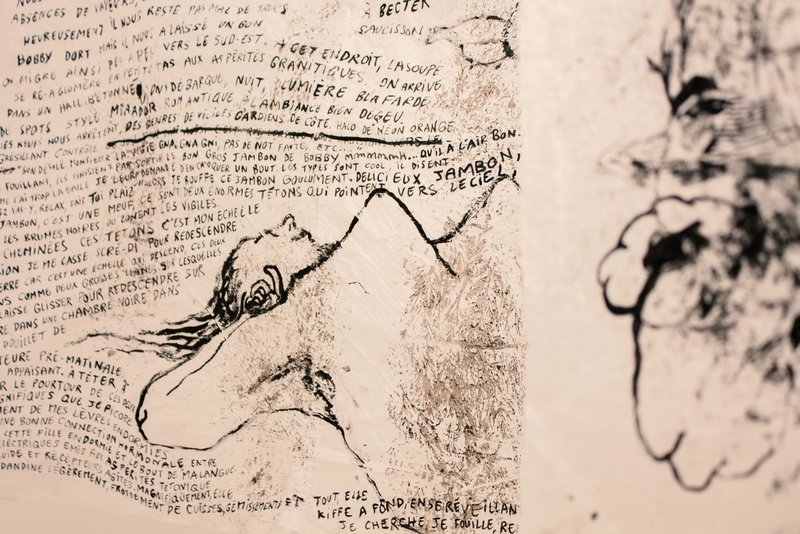

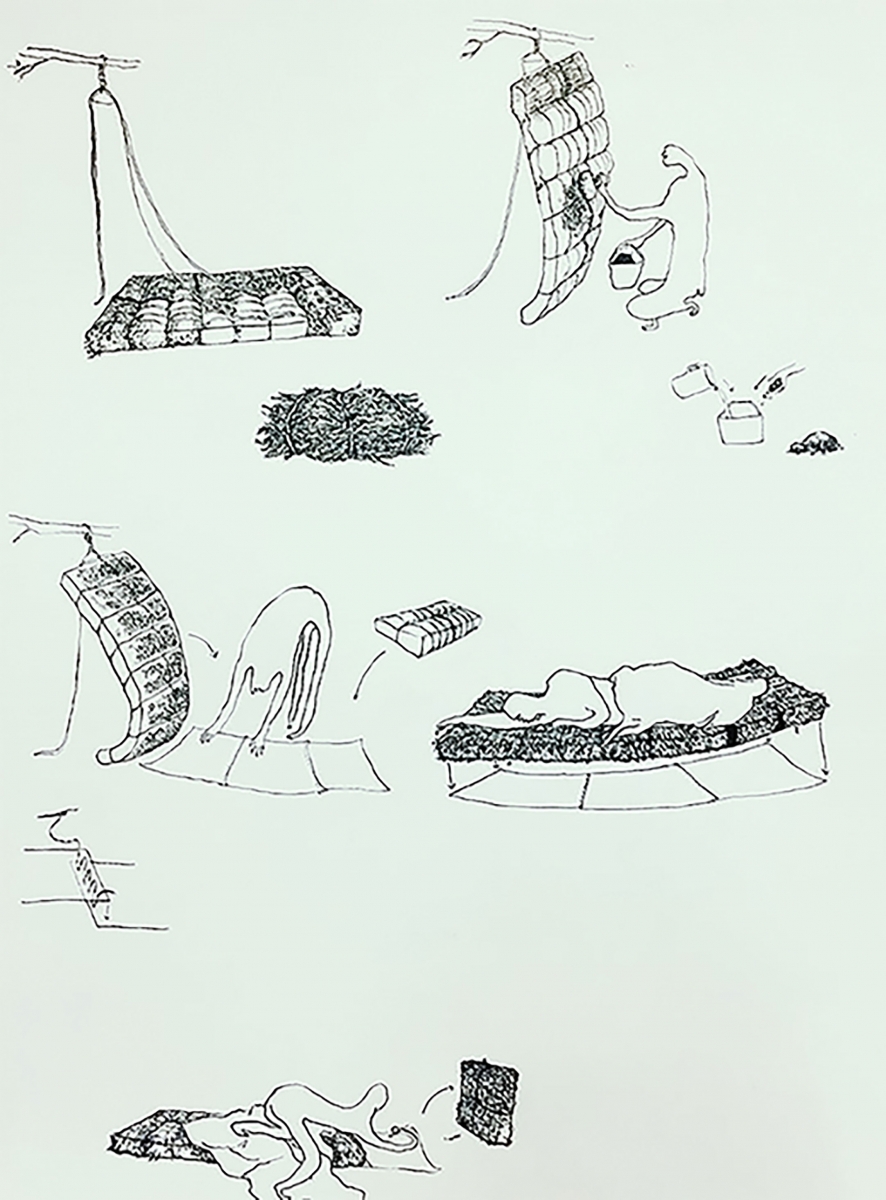

In Saint-Etienne, the trio tried, for two weeks, to live and feed themselves solely on what the city holds, on what nobody uses, waste piled up in wastelands, weeds, dead leaves, and the remains of pruning, food waste, and composts. They turned the Limbes space into their “base camp” where they slept, created, and cooked, in a space that they put together as they found things and according to their needs or wants. In the centre of the first room, a tornado of cardboard boxes, branches, paper, and plastic bottles lay strewn; on the walls, we could appreciate twelve “BioHARDCORE” horoscopes, written by Antoine Boute and illustrated by Chloé Schuiten, decorated with strange zodiac-style statuettes that the young artist had made from oven-baked breadcrumbs. Behind it, a room was renovated as a “cave”, with a mattress made from bunches of boughs; the third room was dedicated to the vital activities that were drawing, dream notation, and food preparation. On the floor, there was an electric hotplate, next to which were found cut-up food waste carefully arranged by type, colour, or finesse, forming an original kind of palette; opposite, Clément Thiry and Chloé Schuiten transcribed and illustrated their nightly dreams using black ink made from coal gathered at the Couriot spoil tip.

We find in BioHARDCORE Capsule what John Cage called experimental, “not as descriptive of an act to be later judged in terms of success of failure, but simply as of an act the outcome of which is unknown”. 3 Here, there is no other objective than that the experience be understood as a process, as a radical modification of conditions and lifestyle; everything is subordinate to it, from the arrangement of the exhibition space to the production of food, or the city wanderings, and chance encounters. It is also experimental in that, during the residency, it was impossible to discern what belonged to the project and what did not, what belonged to artistic practice and what was a lifestyle project for daily life: “the experiment . . . . is not knowing what to call it at any time! Today, we may say that experimental art is that act or thought whose identity as art must always remain in doubt. Not only does this hold for anyone who plays with the ‘artist’; it holds especially for the ‘artist’!” 4

How can we describe this experiment? It strikes us as being a flight within the very interstices of the urban fabric, of laws, norms, and capitalism, using the weapons of recuperation, use of waste, DIY clothing, makeshift shelters, or food recipes, among other things. It is also a kind of return to a wild state of which we find the hallmarks in the relationships of artists to the soil, to plants, omnipresent in the exhibition, in the importance that they give to the forest – on the evening of the exhibition opening, the artists invited the last of the Enlightened to walk on hot coals in the Jardin des Plantes de Saint-Etienne – and to animality. It is an experiment that could be described as romantic: bearing witness to the importance Clément Thiry gives to dreams and sleep, Chloé Schuiten’s considerable interest in mystical connotations and symbols, the deliberately insurrectional character of Antoine Boute’s poetry, and the omnipresence in their discourse of a chaotic and all-powerful natural world as a remedy for civilisation.

The BioHARDCORE revolution is above all a celebration: Antoine Boute, Chloé Schuiten, and Clément Thiry became blithely entrenched and immersed in all of the shit the world supplies in abundance, embodying that mass – the people – that overflows and submerges capitalism itself, embodying the perpetual insurrection that brews within it. However, we do regret the project’s localised, temporary, and partial character – at the Limbes, the water, electricity, internet, and lights were never cut off – as well as its symbolic character. In the ambiguity that is maintained between the poetic and the political, between discourse and practice, lies both the dangers and the virtues of the collective’s approach: it is pleasing to imagine this fiction in action, this poetry of excess progressively colonising reality, seeking in the real world the signs of BioHARDCORE revolution; yet we fear that this is seen only within the strictly delimited perimeter of the artistic sphere. Be that as it may, the experimental and sweeping BioHARDCORE Capsule is only one phase in a process whose next stages of experimentation we intend to follow closely.

Notes

- Lecture held within the framework of the Transport festival / e-festival at the Mutualab in Lille on 19 March 2016 : https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ix8Af3moTGw

- Chloé Schuiten, “Il y a des territoires interdits aux humains. Enfin rien n'est vraiment interdit dans les faits les humains n'osent pas y aller” [Some territories are forbidden to humans. Well, nothing is really forbidden to humans but no human actually dares to go there], http://www.64page.com/2017/01/28/chloe-schuiten-il-y-a-des-territoires-interdit-aux-humains-enfin-rien-nest-vraiment-interdit-mais-dans-les-faits-aucun-humain-nose-y-aller/

- John Cage, Silence: Lectures and Writings, (Middletown: Wesleyan University Press, 2010), n.p

- Allan Kaprow, “Just doing”, in TDR (1988-), Vol. 41, No. 3 (Autumn, 1997): 103.