Thulile Gamedze is an artist and writer, who lives and works in Cape Town, South Africa. She is also member of the iQhiya collective, a network of young women black artists united in defense of their art and the transformation of institutional lines that often privilege the work of male artists unfairly. Activist and aware of her position as a post-apartheid subject, she begins a process of "decolonization of the imaginary" that teaches to see images and representations differently, so that it can become others. His approach tends, in this, to question hegemonic discourse by refusing the stories, practices and conditions imposed as the only truth.

Marion Zilio: In your approach, you set up creative and experimental learning methodologies, making your artistic interventions political demands. To what extent does education proceed from an act of resistance? How does this gesture fit into a lineage linked to the history of South Africa?

Thulile Gamedze: I think the idea that my artworks are ‘political demands’ is an interesting one. I suppose when I make work, my ‘political demand’ is in its process, whether I am making an art object, teaching, or writing, I try to focus on a practice that is intimately connected to the context in which it occurs. In reality, the actual conclusion of an idea is rarely as important as what came before, which is usually a collective process of thinking and sharing – I see this most in education where the workshopping of ideas and the pool of experience are the most essential parts of making. Often we are told that artworks come from an individual so I think being involved with other people, being concerned with a collective - this is political because a capital-driven form of art prefers individualistic thinking and production.

This approach to collectivity is important to me. In this way, I am within a Southern African historical lineage of interdisciplinary and collective artistic practice, which was a huge part of the fight to end apartheid. I am referring to art centres like the Community Arts Project in Cape Town during the 70s and 80s, the MEDU Ensemble- an anti-apartheid collective of cultural workers operating from Gabarone, the FUNDA art centre in Soweto, and so on. Artists from Dumile Feni, to Mongane Serote and Thamsanqa Mnyele. Publications like Staffrider, and SACHED's Upbeat magazine for kids learning under the apartheid 'bantu' education which severely limited them... Although the political situation has shifted in some ways, art still needs to find home in collectivity, sharing, and activism. For me, reading about and having conversations about our art history with people who were involved are ways to constantly see yourself and your own work as part of a longer story of creative resistance. The idea that artists can exist as separate entities from the oppressive systems in place on the continent is a very dangerous myth. It is easy for artists to think that because they use images and make ‘representations’, that they are simply observers and interpreters of the world. However, we are participants just as much as anyone else, and that means we should be held accountable for the ways we choose to make.

MZ: In many of your projects is the "pattern" of Glitch. What does this computer bug mean to you?

TG: Yes! I had a long while where I was interested in the glitch. I still am, but I suppose I use it in less aesthetically-driven ways. For me, the glitch is represents the numerous possibilities of any given image/ video/ thing. The idea that we can edit a digital file directly through coding is exciting- one symbol or letter in a digital code changes the entire presentation of a piece of image data. It is a systemic intervention that reaches into the image, rather than attempting to shift its surface. There must be a metaphor there. Glitches remind me of parallel universes, and working with them allows the idea that there exist millions of ways to construct any given thing. The project where I started with these glitches was a body of work exploring my childhood memories of attending a Christian church in Johannesburg. The memories were often uncertain, blurred, and charged with emotion. By photographing the church and glitching this one image into hundreds of different, equally flawed versions, I was able to think about the complexity of memory, and how our responses to it change over time.

MZ: As an artist and critic, you navigate between theory and practice, what place does aesthetics take here? To what extent does this contribute to decolonizing the imaginary?

TG: I suppose this goes back to thinking about process again. Lately, my writing and art-making is becoming one thing. I have always made these mind-maps to help me when I write a commissioned text that I am confused about. They clear my head. Recently I have started re-working these mind maps and layering them with more images and thoughts, after I am done using them for writing. Mind maps are my thinking tool. For me, they talk about uncertainty and incompleteness, they can be made with people, and they have gaps when you are missing information. They don’t pretend to be conclusive.

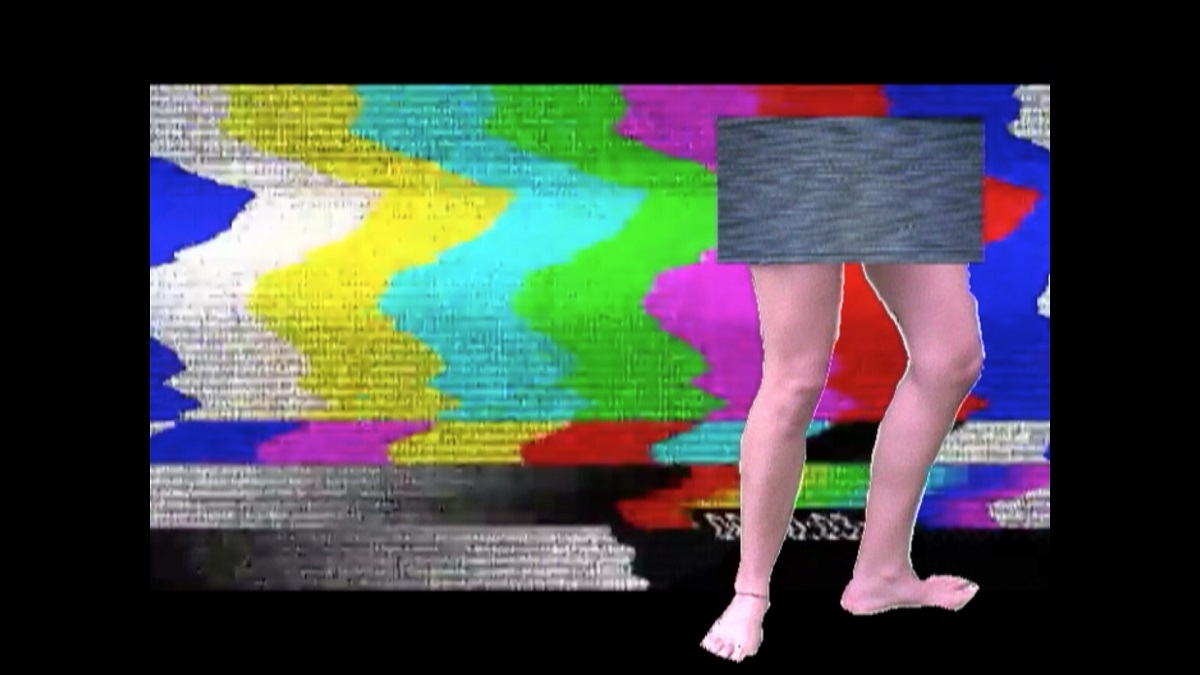

I also make video mind maps, where I ‘teach’ lessons under the alter ego ‘prof gamedze'. In these, I play with aesthetics of online education, but I push it into chaotic representations of knowledge by layering multiple pieces of information.

The aesthetic follows the process, so right now, I am finding mapping interesting and relevant to my work. On decolonization- to some extent, I think our imaginations are one of the only places where decolonial narrative already exists and that’s why everyone is so unhappy!- nothing we imagine is ever reflected back to us. For me, decolonization is about being able to create spaces where our imaginations are safe to do their work. Perhaps collective mapping and thinking is one such place? I’m not sure…

MZ: You were born in 1992, two years before the election of Nelson Mandela, the first black president of the Republic of South Africa. Does this era signify the end of political consciousness in art, if so, why?

This is my argument, although I think many parallel processes of strategic demobilisation began to happen a little while before 1994. 1990 was the year that the settlement between the ANC and De Klerk (that ended apartheid) was finalised. Apartheid was officially over, and that also signified the end of international sanctions and in many cases, funding for resistance movements. Amongst these were radical art and education centres whose work was understood by the international community as solely geared towards the end of apartheid. While this was true, of course, there was still much work to be done, since justice had not been served, and economically, no significant shift in South African resource ownership took place. In fact 23 year later, our economy is even more racially unequal than it was then. It was a moment where we needed collective, and people-driven art practices because the problems of new South Africa are not as easily understood now that our constitution claims democracy. Instead, our art economy became geared toward the global art market, and we lost a lot there I think.

Most of our founding art centres – I would argue those to which we owe much of our contemporary practices to, ran out of funding, and closed their doors in the years leading up to democracy, or shortly afterwards. The ANC was incredibly selective about cultural spaces they kept afloat (as well as having rule over a nation that had been economically and psychologically destroyed without reform), opting for ones that contributed to the rainbow nation story handed out post-1994, and excluding those who recognized that the struggle was not yet over. The image is of prime importance in post-1994 South Africa but - to go back to the glitch - the structure and the coding of that image needs desperately to be repaired.

MZ: Apartheid was a policy of separating spaces according to racial or ethnic criteria in specific geographical areas. In your artistic practice, it seems that you are looking to get out of the institutional grid. What forms does it take?

TG: I think I am interested in the idea that although physical spaces can represent certain ideology, it is possible to repurpose structures and materials to change the way we imagine space. I am not particularly against using any spaces, unless their political load feels too difficult or unethical to engage with. So I am all over - in the classroom, galleries, the web, at bars, and making shows in random spots.

MZ : In France, African artistic scenes are gradually beginning to be the focus of major fairs or exhibitions. How do you imagine the evolution of the condition of African artists on the international scene, in the history and the art market, in general?

TG: That is a very difficult question. We have seen multiple trends in the global art market, with Africa not being the first area of the global South to have become a commodity in the world industry. Of course, it is important that our work is recognised globally, but at the same time, it is important for us to be self-sufficient (to focus on making artist-run spaces for education and experimentation whose work is geared towards the context of South Africa) because the market will shift again, and when this happens, we need to have the infrastructure (psychologically and materially) to ensure that the west is not our only means of income or exposure.